Curator of Engagement and Dialogue Sinead Cox shares the story of a historical quarantine in the summer of 1916.

Although you may have heard (to the point of cliché) that we are living in ‘unprecedented times’ during today’s COVID-19 pandemic, communities across Huron County have seen quarantines and the temporary closure of schools and businesses before. Although usually on a much smaller and localized scale, these actions in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were in response to contagious illnesses that included influenza, measles, diphtheria, scarlet fever, smallpox, whooping cough and typhoid among others.

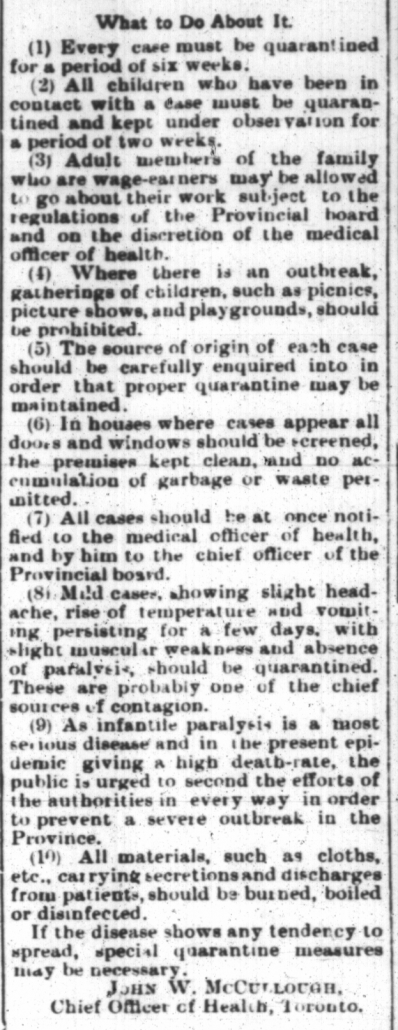

In 1916 an outbreak of infantile paralysis (polio or poliomyelitis) hit North America. The poliovirus is most dangerous to children under five years of age and in serious cases can cause permanent and debilitating nerve and muscle damage to survivors if non-fatal. The 1916 epidemic was particularly devastating in New York and then appeared in Canadian cities like Montreal before eventually arriving in southern Ontario. In Ontario, the provincial Medical Board of Health enacted quarantine regulations and required doctors to report all cases or face prosecution.

The outbreak had reached Huron County by July, when a fourteen-month-old girl in Varna died: only the second fatal case confirmed in Ontario up to that point. Panic hit the next month when three young children in Hullett Township contracted the much-feared disease. The children had come to live temporarily in Hullett (now part of the Municipality of Central Huron) with their parents during the flax harvest, but their permanent home was reported as ‘Muncey Reserve.’ Indigenous families from Southwestern Ontario reserve communities, including those on the shore of the Thames River south of London and also Saugeen First Nation to the north, were a crucial labour force for annual flax harvests in the early twentieth century. Entire families moved seasonally to pull flax for Huron growers; they worked and lived in close contact with each other, camping alongside their worksites.

The sick children belonged to a group of about 15 families living in tents roughly six miles from Clinton when the infantile paralysis struck-eventually infecting two five-year-olds and a two-year-old. A local Blyth doctor treated the first cases and told the area newspapers that the farm workers’ living situation presented a challenge for protecting the lives of the other 23 children in the camp: “Isolation and quarantine, so necessary for the treatment of infantile paralysis, are something hard to enforce in any Indian reservation or encampment…We are doing what we can to prevent any spread of the disease, and watching for further symptoms, but it is next to impossible to enforce the requisite isolation.” The vast majority of poliovirus cases are completely asymptomatic. The disease can spread through direct contact or via contamination by human waste.

For one of the five-year-olds, the virus was tragically fatal on August 25th, but the other two children soon appeared to be recovering. Local newspapers did not identify any of the camp members by name, but a death registration reveals that the little girl who lost her life was Annie Corneolus, the five-year-old daughter of Abram and Elizabeth. She was ill only one day, but the polio had caused lethal ‘paralysis of respiration.’ Her birthplace is recorded as Oneida Reserve (Oneida Nation of the Thames). Annie’s burial took place at Burns Cemetery, Hullett. Local health officials separated the families with sick children from the rest of their neighbours and they proceeded to quarantine at a farmer’s house on the 11th Concession. School Section # 11 at Londesborough cancelled classes for all students as a precaution.

Fortunately, their quarantine appeared successful and there were no further cases reported. The Clinton New Era announced that “the infantile paralysis scare in Hullett Township has pretty well blown over.” When health authorities lifted quarantine the families impacted returned to their reserve community, and the rest of the camp moved on to Blyth to continue their flax-pulling work. The Huron newspapers make no mention of whether or not the surviving children suffered any long-term health effects. Later reports listed the total number of province-wide infantile paralysis cases at 64 for July and August of 1916, with 8 resulting deaths–meaning that 25% of those total polio deaths occurred in Huron County.

There is no cure for polio, but the Salk vaccine of 1955 would eventually be effective and widely used to prevent the disease; after continuous deadly outbreaks throughout the first half of the twentieth century, childhood vaccinations have eradicated polio in Canada.

The living and working conditions of temporary farm workers in 1916 would have made following advice about precautionary hygiene and social distancing almost impossible to follow-and many people in Canada are facing those same challenges today, without equal housing or opportunities to practice self-isolation under novel coronavirus. Although the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic is not the same as polio, the reality that Indigenous communities continue to be disproportionately impacted by pandemics, and that temporary and migrant workers are at a higher risk because of a lack of resources and opportunities to safely distance is absolutely precedented.

More Info about the history of polio in Canada: https://www.cpha.ca/story-polio

*Note: I wrote this blog post using contemporary newspaper accounts including the Wingham Times, The Wingham Advance, The Lucknow Sentinel, The Clinton New Era, The Clinton News-Record, the Signal (Goderich) and others, all accessed from Huron’s free historical newspaper database: https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers/ Annie’s death documentation was accessed via Ancestry.ca (Archives of Ontario; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Collection: MS935; Reel: 220). All of these accounts were written from a settler point of view (as is my own), and the newspapers did not include the voices or even the names of the community members impacted. If you have any further information you’d like to share about this outbreak or similar outbreaks in the past contact museum@huroncounty.ca.