Kyra Lewis, Huron Historic Gaol outreach and engagement assistant, explores the architectural history of the Huron Historic Gaol.

The Huron Historic Gaol is a one of a kind building: predating Confederation, this anomaly has stood for over 181 years. Despite being made of predominantly stone and lumber, it has survived fires, being struck by lightning twice, and a tornado. However, its survival is not the only thing which stuns visitors about this incredible building. The Gaol’s architecture is one of the only of its kind in Canada standing today. This blog post will explore the architectural history of the Historic Gaol, and how and why its structural significance is honoured 181 years later.

Settlement began in Goderich as a result of the development of the Huron Tract in the 1830s; at the time, Goderich and the surrounding area were part of the London District. However, residents in the area felt disconnected from the district government and their affairs. Back then, in order to qualify as a County, you must possess a local government, and to do that, you had to have both a Courthouse and a Gaol. So in 1839, a contractor named William Geary began clearing land allocated by the Canada Company to build a Courthouse and Gaol, with the grand objective of establishing a local government for the County of Huron. The location was decided based on the fact that, at the time, the Gaol was situated outside the town. The location of the Gaol was considered ideal as it was distant enough to host undesirable residents, but still close enough to town for the convenience of court officials.

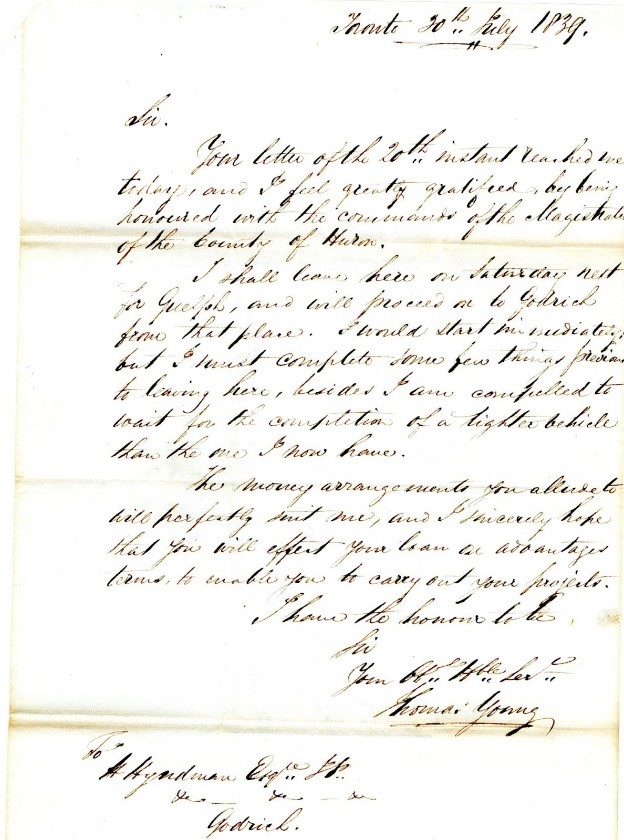

Letter from Thomas Young expressing his opinion and pleasure to take on the Gaol contract for Huron County.

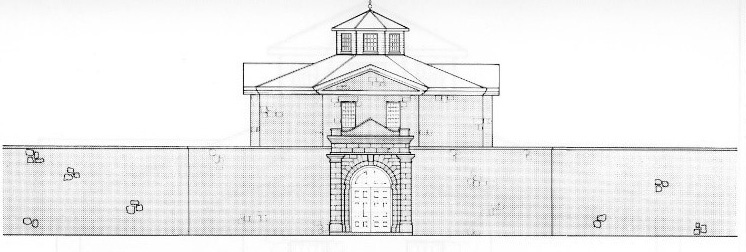

The project was given to Toronto architect Thomas Young. Young was born in England and had emigrated to Canada by 1834; until 1839 he was a drawing master at Upper Canada College. He received many commissions, one of which was to design King’s College in Toronto, which was completed in 1845. Young also received several other commissions between 1839-1844 to design, including the Wellington District Gaol and Courthouse, the Simcoe District Gaol, the Guelph Courthouse, and the Huron District Gaol. Many of Young’s designs were inspired by historic architecture, paying homage to neoclassical styles he utilized as an artist. This style consists of grandeur and symmetrical designs, similar to that of Roman and Greek buildings such as the Pantheon, located in Rome. Neoclassicalism became extremely popular in Italy and France in the mid 18th century, and was a very prominent influence in Young’s architectural designs and drawings.

Building materials for the Huron Gaol were sourced locally or imported via schooner from Michigan. A public posting requested “400 Cords of Stone – District of Huron Contract”, it was stated that the stone could be no less than “12 inches thick for the building of walls 2 feet thick”. This local stone came from the Maitland River, which flows through Huron County just to the north of the building. While local stone was used to construct the walls of the Huron Gaol, “coping and flagging” stone, which was predominantly used around the windows of the Gaol, was brought in from Michigan. Many other tenders were let for the project, such as 4,500 board feet of hewn timber, as well as blacksmith work and plastering.

Drawing of the Huron Historic Gaol from Nick Hill’s report Huron Historic Gaol Goderich: A plan for restoration

PRISON REFORMATION

Young’s design for the Huron Gaol was inspired by Jeremy Bentham, an English philosopher. Bentham was devoted to reformation and rehabilitation and was curious about how prison design could contribute to the reform of criminals. Bentham popularized the panopticon, meaning “all seeing,” which precisely reflects the intention of the architecture. Panopticon designs allowed Gaol staff to observe prisoners from a centralized point, without the prisoners knowing when and if they are being observed. This structure was created to enforce compliance on prisoners, as they always had to act as though they were being watched. Due to the threat of constant surveillance, the theory of this design suggested that prisoners would then behave and conform to ideal behaviour. The invasiveness of always being able to be seen was stressful for prisoners, and thus they were more likely to comply with reformed behaviour. This was the intent of prison reformists such as Bentham, as their main objective was to create functional prisons that ran on limited manpower, but generated successful results concerning rehabilitation. Bentham believed that learning skills and completing tasks accurately and effectively while in a panopticon prison would ultimately contribute to their rehabilitation and readmittance into society as a better person.

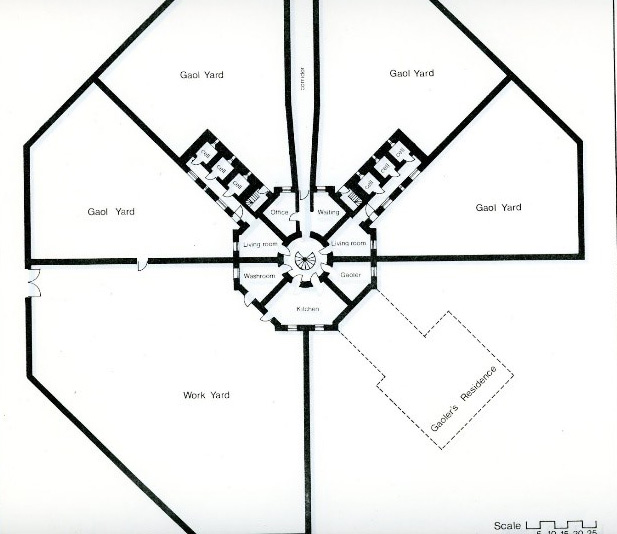

The panopticon was very prominent in the Gaol’s original design, as the Gaol itself has a centre building, with walls jutting out like spokes on a wheel. This was obviously intentional, as the third floor cupola allowed for staff to see each courtyard from one centralized point. Prisoners in the yards were therefore always observable, so there was an immense amount of pressure to behave. However, the cupola was not utilized nearly to the extent it would in a classical panopticon structure. The building’s courtyards were the only instance where panopticon design was implemented, as the rest of the building used a separate system. For this reason, the architecture still allowed for prisoners to have some sense of privacy and independence when in their cells. Thus Bentham’s ideology was not entirely encapsulated within Thomas Young’s design of the Huron Gaol, as only one aspect of the Gaol operated with this level of surveillance. Architect Nick Hill regarded this in his 1973 report to Huron County Council, mentioning that the design had “remarkable geometric clarity and functional arrangement based on the octagon”.

Another systematic influence that was used in the Huron Gaol’s design, was the separate system. This concept, oddly enough, was actually a contrast to the panopticon design. It enforces that prisoners stay isolated from one another, and can only be seen by guards when they enter the individual prison blocks. While the panopticon design was utilized in the structural elements of the courtyard, the separate system was incorporated within the Gaol’s cells. The act of keeping prisoners separate was significant as the Gaol was particularly small. This method ensured there would be fewer issues concerning fights and other conflicts amongst the prisoners. Solitude was also a major influence in many forms of prison reform around the 19th century. This form of confinement was designed to make prisoners easily controlled. Maintaining a sense of loneliness and isolation allowed for prisoners to feel more vulnerable and thus more compliant to the whims of the system they were incarcerated in. Eliminating that sense of unity and togetherness with other prisoners, in theory, would alleviate the possibility of revolts and violence as well.

The Huron Gaol implemented this in its cell design. There are four different cell blocks, with corresponding day rooms. Blocks one and two are on the first floor, with blocks three and four located on the second floor. The third floor, where the courtroom stands, has four individual holding cells. Every cell is oriented facing one direction, so other prisoners within the same block cannot see each other when in their individual cells. Historically, women and men were separated into different blocks, as mentioned in the Rules and Regulations of the Huron District Gaol detailed in 1846. This document stated that male and female prisoners were to be “confined in separate cells, or parts of the prison…as far as the dimensions, plan, and accommodations may allow”. At this point in time, prisoners were also separated into “classes” which were generally not permitted to intermix. For example: “1st. Prisoners convicted of felony. 2nd. Persons convicted of misdemeanors and vagrants. 3rd. Persons committed on charge or suspicion of felony. 4th. Persons committed on charge or suspicion of misdemeanors, or for what sureties; and in cases where necessity may require it, and circumstances admit, the sheriff may confine female prisoners in the rooms set apart for debtors. 5th. Debtors and persons confined for contempt of court on civil process.” The distance between each cell block also provided a sense of seclusion to ensure the safety of inmates.

The Gaol was a significant building for many reasons, however one of the most significant was the newly implemented techniques centred around prison reform. Prior to Jeremy Bentham and other incredible architects, sociologists, and philosophers, prisons were not based around reform. Prisons prior to the influence of such forward thinkers, were incredibly inhumane, as the concepts of rehabilitation and amelioration were relatively modern concepts in the early 1800s. There were a few gaols that implemented this philosophy, such as the Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, Auburn in New York State, as well as one in California. Thus, when Thomas Young utilized Bentham’s ideologies, it was one of the very first prisons existing at the time to be influenced by the new age philosophies of rehabilitation. Despite the Huron Gaol being of a much smaller scale, its design was truly revolutionary and ground breaking for its time.

Architect Nick Hill observed these concepts when he reflected on the Gaol’s structural uniqueness in the 20th century. Hill evaluated the significance of Bentham’s efforts of reform; “They engendered an attitude towards prisoners which saw the conclusion of exile, flogging, branding, maiming, the stocks and pillory, drawing and quartering.” The social changes these prisons inflicted on society were no small feat, as it signaled changing preconceived norms surrounding prisoners and criminal punishment.

Despite the Gaol’s incredible advancements in prison reform, there were several instances during its long history when councillors approved improvements be made to the Gaol to ensure functionality and proper treatment of prisoners. As there were no facilities for the elderly or the homeless until 1895 when the House of Refuge was constructed in Huron County, the Huron Gaol became a place of refuge for many. At its highest capacity, the Gaol held over 20 people, despite only having 12 cells and four holding cells. Its expansion became a necessity in order to ensure the Gaol was capable of executing the needs of all its inhabitants. For example, in July of 1853, the walls of the Gaol were deemed “insufficient for security” by the Grand Jurors. Despite this topic being brought to the Council’s attention in 1853, the Gaol walls were not expanded until July of 1861.

The renovation to the walls was undertaken after the Canada Company formally transferred the Gaol land to the County of Huron. Recommendations arising in 1856, following concerns around escapes from the Gaol, led to the walls being extended by two feet in height with loose stones being installed at the top of each wall. These stones were meant to come loose if a prisoner attempted to escape, causing them to fall to the ground when they grabbed a loose stone. William Hyslop was hired as contractor to renovate the walls, and was paid 27 pounds, 12 shillings, and 6 pence for “repairs to the Gaol wall”, as documented in council minutes from 1855. In the 1862 council minutes, William Hyslop is recompensed again for his efforts on the Gaol walls, after the County purchased the surrounding land to extend the walls outward, expanding the yard. The walls, as they stand today, are 18ft high and 2ft underground to ensure no prisoner could go over them or tunnel beneath. Other major improvements of the Gaol included the installation of a slate roof, as well as a bathtub in 1869. The original wooden bathtub was upgraded to copper in 1895 and a flush toilet was also installed. These changes were made for the health and well-being of the inmates, as health and hygiene were only recently being regarded as a necessity. Especially to avoid sickness and disease spreading through the relatively small facility.

The Huron Gaol has had an incredible 181 years of history in the County, and its captivating architecture represents incredible structural and architectural innovation for its time. The Huron Gaol is not only an incredible piece of history, but an amazing representation of the evolution of prison reform, rehabilitation and human rights.

Online Sources:

- https://read-the-plaque.appspot.com/plaque/king-s-college

- http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/young_thomas_1860_8E.html

- http://dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org/node/428

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bentham/#Pan

- Fowler, Megan. “The Human Factor in Prison Design: Contrasting Prison Architecture in the United States and Scandinavia”. 103rd ACSA Annual Meeting Proceedings, The Expanding Periphery and the Migrating Center. Iowa State University: 2015.

Primary Sources:

- H. Belden & Co. “Illustrated Historical Atlas of The County of Huron ONT: Compiled Drawn and Published from Personal Examinations and Surveys”. Toronto: 1879.

- Lizars, Daniel. “Rules and Regulations for the Huron Gaol 1846”. Rowsells and Thompson Printers. Toronto: July 24th 1846.

- Hill, Nicholas. Huron Historic Gaol Goderich: A plan for restoration prepared by Nicholas Hill. Undated.